Step back for a second and think about the miracle you are trying to create when you perform a song with people who might never have played with you before, might never have played with each other before, and might never have heard your tune before. When things go well the miracle comes true, and this newly assembled group of people can join forces with you to create a genuinely beautiful public performance with no rehearsal. It's amazing, stunning that it ever works at all, really. So realize it's a fragile thing that must be nurtured and cultivated. Be willing to prepare in service of that cultivation.

A great rhythm section with players who know all the tunes ever written (and there are some rhythm sections like this!) will not need your help and will stand a good chance of making you sound great if you can just come in at the right time and in the right key. But much more common are rhythm sections made up of musicians like me who only know a few hundred to a few thousand tunes, and are more comfortable with most of them in some keys than in others.

Even we players with skills that don't always measure up have worked hard getting to the point where the miracle is within reach. We have studied music theory. We understand rhythm. We have trained our ears and brains to hear what the music is doing, and we have trained our bodies to create on our instruments the tones we hear in our minds. We have spent countless hours practicing, studying, listening, attending classes, and taking lessons. Many of us have focused our lives for years at a time on the development of skill in music performance.

Most singers appreciate all this and do not need to be reminded. Some have made similar commitments in service of their vocal craft. But there are also the uninformed few who sang a night of karaoke a few months ago and were told by a drunk, horny person hoping to pick them up that they sounded nice, so now they feel ready to front the band and collect the glory without really knowing the first thing about what they are doing. It is unreasonable to expect everything to go smoothly if you haven't worked at the music a bit.

Very often you will be asking a rhythm section made up of people like me to play a song in public for the first time when we have never heard the song before. If you do the right preparation, the miracle of beautiful music in that situation is possible. A few basic steps can really help a lot. Some steps can be left out some of the time and things might still go OK. But the more you omit, the more you are tempting fate.

Another benefit of preparation is that it puts your relationship with the band on a good footing. It shows that you understand your job as a singer and their job as a rhythm section supporting you. It shows your professionalism and earns you respect.

So here are some specific things you can do to prepare for that time when you drop a chart in front of players you just met, count off the tune, and knock the socks off your audience.

- Listen to music a lot. Listen to jazz. Not just vocal jazz, but real, instrumental jazz. Learn to identify where you are in the tune. Learn what different kinds of introductions and transitions sound like. Learn to count beats and count bars. Do all these things with music that challenges you and makes you work at it.

- Learn at least some music theory. The more the better.

- Learn solfège, i.e., train your ears well enough that you can sight-read music without an instrument in front of you. You might have a nice voice, but you are not really a singer if you can't do this at a basic level.

- Understand time and tempo. Learn how to count to four, eight, or even higher at a steady speed. Understand that the band is going to play your tune at the speed you count, so you need to be able to hear the tune in your head at the speed you want, and then count at that speed.

- Learn the names of a few feels that apply to common tunes. It will help you a lot to be able to use words like Latin, Bossa, Swing, Shuffle, Two-feel, Samba, Walking Bass, Rubato, Clave, Straight Eighths, and so on. The vocabulary goes really deep. I was rightly scorned on a gig because the drummer used the term "Partido Alto" and I didn't know what it meant. There is always more to learn, so get started now if you haven't already. These terms are not just in-group jargon; they're ways of communicating complicated ideas quickly on the spot.

- Choose keys that are comfortable for you, but also consider that standard keys are better than bizarre ones. If your voice fits "On Green Dolphin Street" in E major, think about the fact that the tune is usually played in E-flat major and maybe you could simplify things for everyone by choosing the nearby standard key. It's one less thing to go wrong.

- Also on the subject of keys, it's handy to know that because of the way it has evolved around horns, jazz leans much more toward the flat keys than the sharp keys. There are a few standards normally played in sharp keys, but not many, and not too deeply into the sharp keys. Going deeply into the flat keys, by contrast, is much more usual. So all else being equal, a chart in a flat key is probably easier for your band to read and play than a chart with the same number of sharps. All music students learn that we should be equally comfortable in all twelve keys on every tune. Very, very few of us come anywhere near achieving that goal. Let your choice of keys live in the real world of musicians who actually exist.

- Know what makes a good lead sheet and try to have a good one. A good lead sheet:

- Is written in the key you want to perform the song in.

- Fits on one page if practical.

- Reflects the harmony you actually want to use for your performance. If you find a tune in a cheesy fake book somewhere, keep in mind that its changes might not match the super hip changes on the record you are singing along with to practice. If you want the hip changes for your performance, get them on paper for the band. If you have never even heard the changes on your lead sheet before you hit the bandstand, you're going to have a bad time.

- Includes all the parts of the song that you intend to do, including introduction, verse, chorus, and ending, if applicable. As I said above, some of these steps can be skipped sometimes. A good rhythm section can make up a credible introduction or ending to most standard tunes on the spot, for example. But the results are often better if this isn't left to chance, particularly if there's a particular progression you're used to hearing so you know where and how to enter.

- Is clearly written or printed, with good contrast, in a clear font of sufficient size, and without major printing blunders. A singer recently gave me a lead sheet where many of the chord symbols had the tune's lyrics printed over them.

Remember that the people reading your lead sheet will probably be facing bright stage lights and might not have realized they would need those little lights that clip on their music stands. - Contains clear guides to the form of the tune, such as heavy bar lines between sections, and is free of confusing errors. A singer handed me a chart that was missing two bars from one section. The bassist knew the tune so he played those two bars when the time came, even though they weren't on the chart. The drummer and I didn't play them because we didn't know the tune. Carnage ensued on the bandstand. Another chart had a heavy bar line one bar away from where it should have been, causing me and the bassist to get confused about the form at different times. Carnage again. Better players would not be thrown by these errors, granted. But don't you want to maximize your chances of success?

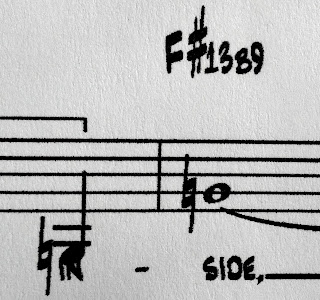

- Uses standard notation. I was recently given a chart where half-diminished chords were written as "C-7b5" which is fine except that the lower-case 'b' doing double duty as a "flat" symbol was printed in a small-caps font, so it looked like "C-7B5."

Nonsense! (Also notice that the lyrics are printed over a note head in that example!) It can be deciphered, but it's unnecessary cognitive load on the person trying to sight-read your lead sheet. Don't do that. Similarly, there is some music software out there (Sibelius, maybe?) creating lead sheets where the 'm' that's supposed to signify a minor chord looks like an upper-case 'M.' Upper-case 'M' normally means major. So it is always extra work to realize that "CM7" on such a sheet actually refers to a minor chord. Avoid software like this. - Contains cues allowing the rhythm section to understand where you think you are in the tune. Cues can be short landmark phrases from the lyrics, a written-out melody or portions of the melody, or whatever. Just something that allows the band to know whether everyone is in the same place, or even performing the same song. A singer recently handed me a lyrics-free chart for an unfamiliar tune. She has a gorgeous voice and a very strong interpretive element in her singing. She performed beautifully, but her interpretation of the melody was so far from what was on the chart that many questioning glances flew between me and the other instrumentalists. The bassist and I knew we were together, but we didn't have any idea whether the singer was with us or on some other planet. It turned out everything was fine, but a few lyric cues on the chart would have made things more comfortable.